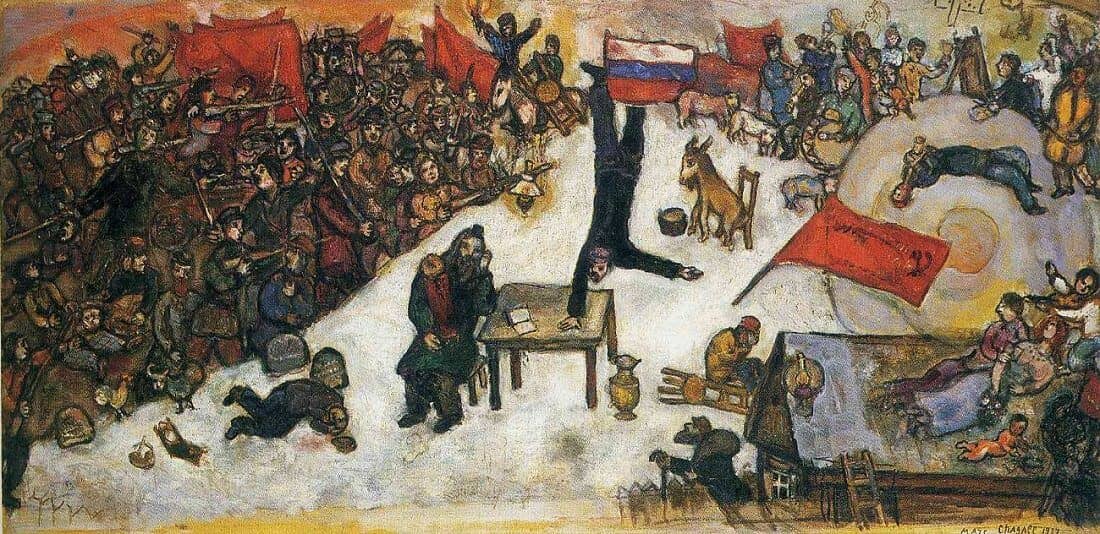

The Revolution, 1937 by Marc Chagall

Fascist assaults on the very core of human morality had been answered by Pablo Picasso in what ranks as the finest product of committed historical art in the twentieth century. His Guernica expressed the full depth of protest that civilization was compelled to make when confronted with political cynicism, and in 1937 the painting was (sadly enough) a major attraction at the World Exhibition in Paris. That same year, Chagall documented his own commitment in The Revolution, an elegiac work to match the Spanish artist's direct accusation. Chagall's painting is not a response to a specific event, but an attempt to articulate political disquiet and unease in his own terms. Two ways of grasping or shaping the world are juxtaposed in antithesis. To the left, revolutionaries are seen rushing the barricades, their red flags proudly proclaiming the victory of Communism. To the right, this image of unity, standing for political demands for equality, is counter-balanced by the free play of the human imagination. We see musicians, clowns and animals playing, the customary loving couple are lolling on the roof of a wooden hut, and in typical Chagall style, the force of gravity has been suspended so that the ubiquitous energies may develop freely. The figure of Lenin links the two zones; balanced acrobatically on one hand, he is showing the revolutionaries the true way to a world of individuality.

"I think the Revolution could be a great thing if it retained its respect for what is other and different," Chagall had written, summing up his Russian experiences in the light of his view of himself as artist. The creative power of the individual is the driving force in the struggle for political liberty. But the old Jew in Solitude still sits thinking about his own future and that of his people ...

The painting is vehemently programmatic, and overloaded with significance, so that its capacity for atmosphere and mood has been lost. Its ambitious attempt to find a general, supraindividual relevance and its unsatisfying treatment of the technical problems remind us of Chagall's zeal in his early works: the juxtaposition of archetypes, of symbolically laden shorthand images of the world, is not equal to the task of rendering the complexity of events. Nor was Chagall himself ever satisfied with this answer to Picasso's great masterpiece. In 1943 he was to redo the large-format version of 'The Revolution' in three panels, blending the political and religious symbolism in the form of a triptych. The smaller version reproduced here was preserved to testify to the artist's direct involvement with world events (quite distinct from the wish to create timeless works of art).