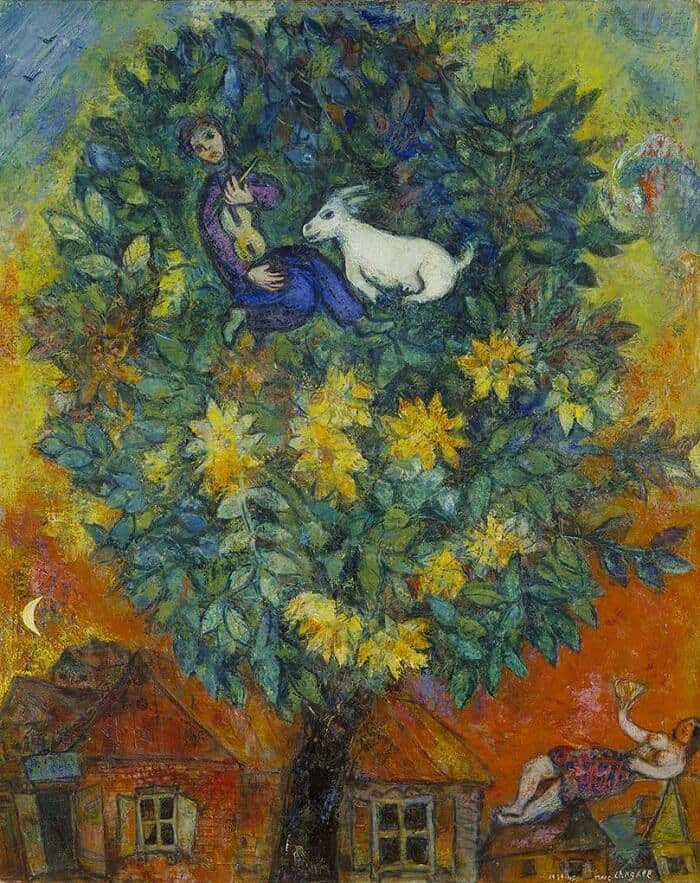

Autumn in the Village, 1939-45 by Marc Chagall

The subject matter of I and the Village re-appears in the work Autumn in the Village. Once again we see archetypal figures which personify a quality of simplicity in a visionary setting: human and animal figures, and a sense of idyllic security, constitute the genre's sine qua non. However, the geometrical grid that made the juxtapositions in the earlier painting possible has now been replaced, in compositional terms, by a principle of free association.

What inspired this painting was not so much rustic life in Russia (which Chagall, after the things he had experienced during the Revolution, was less prepared to glamourize than he had been previously) as an image Chagall had of himself. The atmospheric content of the colour scheme, and the relaxation of the strict grid, are a commentary on his own early period, viewed from the vantage point of the latest aesthetic trends. Surrealism had replaced Cubism, and Chagall felt an affinity through the liberation from self-imposed patterns of order and the reckless espousal of the kind of disorder that is typical of dreams.

"Chagall, and only Chagall, provided painting with the triumphant advent of metaphor." Thus Andre Breton, singing Chagall's praises, and eulogizing his poetic qualities, as late as 1945. Nevertheless, Chagall's relationship to the Surrealists was torn, whatever their theoretician-in-chief might say. Long before them, impelled by the elemental power of his homeland's folk art, he had discovered the significance of dreams, visions and the nonrational for his own work. The Surrealists, whose antirational approach to art drew upon similar sources, repeatedly tried to win Chagall over, but Chagall saw their homage to the power of the unconscious as a way of pandering to the currents of taste and a wilful parade of illogicality, and was unable to identify with them. His artistic credo came straight from the heart: