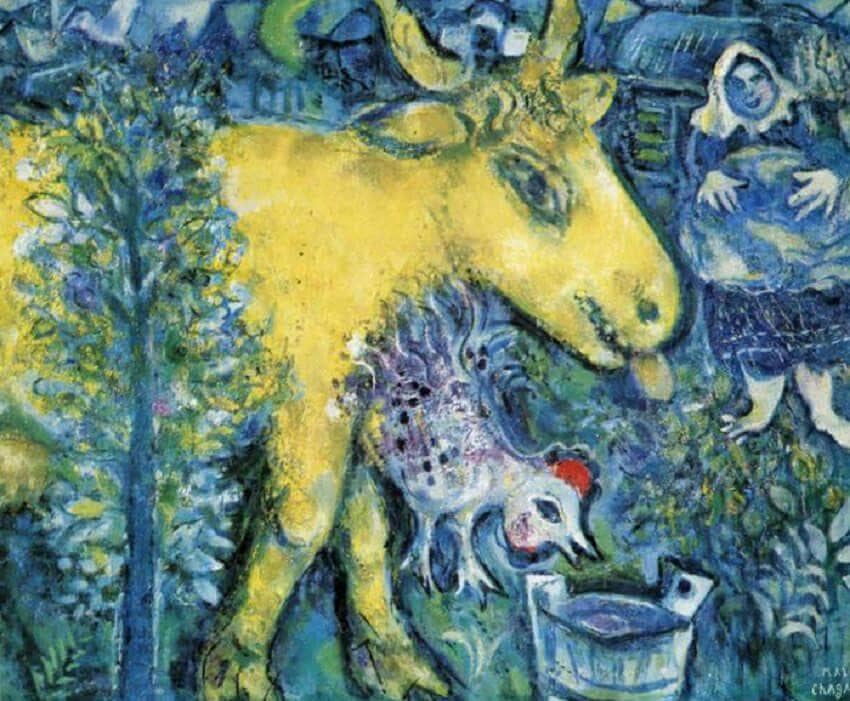

The Farmyard, 1954 by Marc Chagall

In general, forms become more massive in Chagall's later pictures, which is in accord with the expansion of color into larger areas. One can even assume that it was just this effort to achieve a more intensive coloristic use of the picture plane - an effort which was considerably increased in Vence - which called for large solid forms to support the development of color. And in response to this, as a countermove, there is a more compact, ornamental, and lively treatment of the surface design, which is spread like a richly embellished carpet around the large areas of color. If in Chagall's earlier burlesque scenes the medley of fabulous beasts and bizarre performers went tumbling head over heels and filled the entire surface, inducing the color itself to vault and dance, now we find that the merry uproar and roguish humor which characterize Chagall's sense of humanity so charmingly are becoming calmer, more tender, and wiser.

The burlesque theme! It moves in colorful and festive procession throughout Chagall's entire oeuvre, and makes us smile when we think of his picture world, but it has also caused insensitive critics to put this great painter- poet into a corner with fairy-tale tellers. Chagall's humor and delight in the burlesque is never crude, offensive, or caricaturizing. He is full of tenderness and affection toward the funny side of nature and living creatures; he exaggerates and fondly puts the finishing touches on their amusing antics, playfully moving in those spiritual heights which are the home of A Midsummer Night's Dream or The Magic Flute. Like Paul Klee, he is delighted when occasionally humor overcomes grief.

For Chagall, the burlesque theme was linked from early days with the rural idyll. In the backyards of Vitebsk he had opportunity to understand the good-natured grumbling of the cows, the bleating of the goats, and the cock-a-doodle-doo of the roosters as a merry song of praise to the existence of creatures in harmony with nature. Ever since then, the apotheosis of the simple rural existence has been a recurring theme in his dream of life.

In addition, for Chagall the animal -and in this he is comparable to Franz Marc - is the creature which has always, uninterruptedly, been part of the great circle of nature which man has abandoned through willfulness, contradiction, and passion, falling victim to sin and grief. For Chagall the animal represents harmony and contentment with the cyclic destiny of nature; the innocent acceptance of being a part of nature's great ensemble of living things.