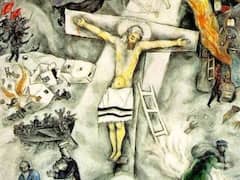

Scene Design for the Finale of the Ballet Aleko, 1942 - by Marc Chagall

At first New York City fascinated Chagall immensely. He went drifting about in it with a feeling of awe, as if in some gigantic piece of antinature. He never learned to speak English, but conversed in Yiddish with the small Jewish shopkeepers and artisans of Manhattan. More often than not they must have talked about Russia and the war, because whenever he returned to his studio afterwards his mind was always full of the martyrdom of man, tragic scenes of war, and conflagrations.

It was just as well for him, therefore, that in the spring of 1942 a commission came his way which steered his fantasy in a completely different direction. Leonide Massine, the famous Russian choreographer, was at that time engaged in staging a performance by the New York Ballet Theater of the ballet Aleko - to the music of Tchaikovsky and after the poem The Gypsies by Pushkin - to be given in Mexico City. Massine commissioned Chagall to design the scenery and costumes. For months on end the two Russians together worked out the ballet down to the last detail, completely caught up in the elevated intellectual atmosphere of their homeland. At the beginning of August the company moved to Mexico City, where the performance was staged on September 10. It was here that Chagall painted the four gigantic backdrops and, together with Bella, supervised the production of the costumes. He had brought the sketches with him from New York.

The reproduction shows one of these, the sketch for the backdrop of the finale. Only in a metaphorical sense has it anything to do with the story of Pushkin's poem, which tells the tale of a young poet who, after becoming a member of a gypsy band, falls in love with the leader's daughter; betrayed by her, he kills her and her lover and is banished by her father. For the final stage setting, Chagall had in mind a kind of tragic apotheosis of the art of poetry. He painted a wide prospect showing a town view of Italianate character on a red ground, alongside which, curiously enough, extend the broad low Alpine houses of Savoy, as if the painter were recalling the landscapes of Europe which he had seen on his last visit. To the left, a cemetery on a hill rounds off the landscape. Above the burnt-red of the earth stretches the vast expanse of the heavens, blackened by storm clouds. A white horse with a two-wheeled cart, looking like a battle chariot of the Homeric Greeks, hurls itself through the stormy darkness; its faintly classical appearance stirs a memory of Pegasus, the winged horse of the muses. The bright shape surges up toward a warm golden circle, bearing the seven-branched candelabrum, which lights up the somber sky like a star of consolation. Thus the fate of young Aleko, of whom Pushkin wrote, called up a response in the fantasy of Chagall, not in any particular detail but only in its general sense - as a symbol of the poet's soul which, refined by suffering and death, comes at last to its deliverance. The color, in the threatening confrontation of red and black, fills the legendary background scene with pathos.