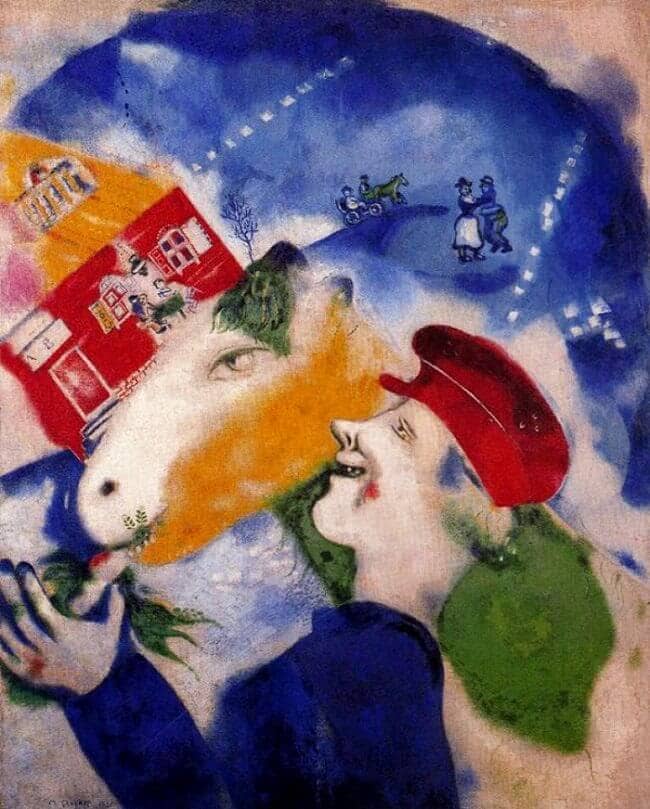

Peasant Life, 1925 - by Marc Chagall

Peasant Life, 1925 is the cheerful picture of country life here. In the foreground a gay young countryman in the blue working jacket of the French peasantry, but with a Russian visored cap, is feeding his amiable little pony a sugar beet. Behind them is the curving panorama of landscape and sky, a great arc in which there is a variety of separate little scenes, regardless of the normal vertical position. To the left, following the extension of the diagonal of the horse's neck, is a red Russian log house. Portrayed in true Chagallian fashion, it allows one to see straight inside; there, beneath a hanging lamp, is a small group of men in animated discussion. To the right, along the rounded horizon, a gentleman and his coachman drive off in an elegant chaise. A droll little peasant couple hops and dances in the open field. The whole merry scene might form a general background to the adventures of Gogol's arrant swindler Chichikov, and for all we know he might be the gentleman in the chaise. In fact, all the individual motifs of Russian folklore can be found again in the Gogol etchings.

But the light and the colorful atmosphere in which the objective details of the picture here seem to be bathed are far from Russian. It is the silken blue of the French sky that strikes the basic chord that resounds through the entire orchestration of color; it is the silvery light over the French landscape that casts its luster over the picture like an immaterial fluid. The rich variety of the colors is absorbed in this hazy gleam, and their volume of tone is reduced to a restrained harmony of richly differentiated hues. Chagall as a colorist has suddenly stepped into the tradition of great French landscape painting, which began with Edouard Manet and was introduced into twentieth-century painting by Paul Cezanne and Claude Monet. Not that Chagall would have specifically had in mind this or that great master; first the astonishing encounter with the natural loveliness of France would have affected his sensitive eye almost unconsciously, and only later would he have perceived the logical connection with the French masters.