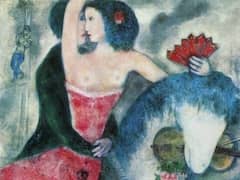

Lunaria, 1967 by Marc Chagall

Soon after Chagall had moved to Saint-Paul-de-Vence in 1967, he painted two very calm and for him quite unusual pictures. These are two still-life paintings with large flower arrangements which fill the entire picture plane. Without any figures or the extra anecdotal touches with which he had previously delighted to adorn his flower pieces, they evoke nothing but the peaceful existence of the flowers themselves. Behind the flowers is a view of the bright but still empty studio, with a large window opening on to a little grove. As if the painter were listening to this calmness and wanting to take possession personally of his new home, he has left his entire mythical entourage outside and has begun only with the feeling which he has always had - a deep veneration of the beauty of nature.

The still life reproduced here shows a large bunch of lunaria stretching out across the entire surface of the picture like sparkling foam. The silvery flicker sets the color tone and modulates the entering light in the finest and lightest gradations. Daintily and fleetingly, by the swift rhythm of the brush, the foliage takes shape and, like a swarm of butterflies, plays against the flaky brightness of the white. The light seems to set the plane into pulsating motion and conveys a sense of movement and transparency without any special perspectival aids. Even the window, which should be the source of this light, is indicated by only the thinnest strokes and seems to cling to the surface. Thus out of the color alone streams the light of the picture. Below, standing solemn and lovely in the center, is a pot of purple cyclamen, its brilliance brought out by a complementary green. The strong accent of these purple flowers shows up the flaky glitter of the white and also forms a delicate association with the four pink, still-covered, discs of lunaria. At the left, magnificently drawn, is a basket of golden-yellow fruit, which leads to the complementary blue of the window zone. The color scheme is quite restrained and is always in keeping with the shining white of the lunaria; there is more a play of feeling than an exercise in color sequence.

Despite this restraint, the picture is a masterpiece of color. One might call it "impressionistic" but miss the point altogether, since every dab of color means not only the thing itself but also the poetic aura lying in and around it. The color transforms reality into its poetic counterpart. In the new studio, which Chagall greeted with a festive bouquet, a bold and free development of color was going to take place.