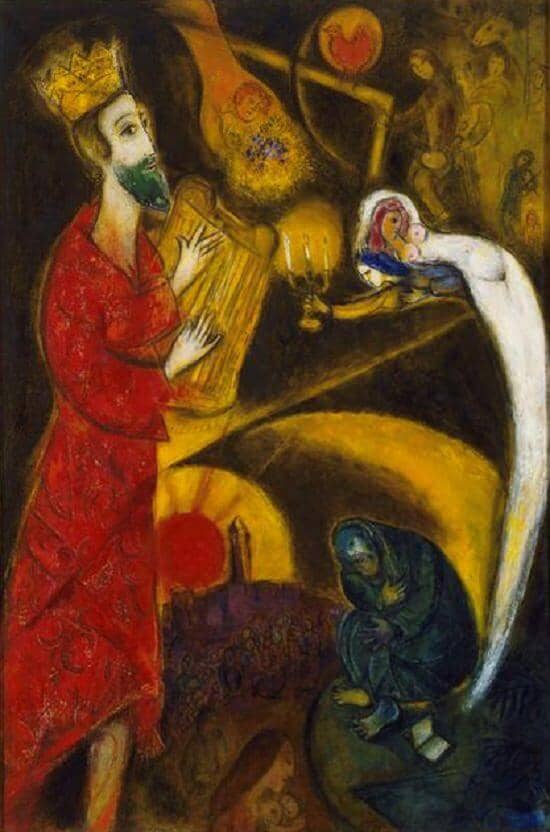

King David, 1962 - by Marc Chagall

Although it was not until the 1930s that Chagall began to develop his biblical picture cycle, he had been familiar from infancy with the Bible as the history book of the Jews. Like a string of pearls threading his childhood days, the Jewish festivals, full of secret expectations and pleasantly awesome thrills, constantly brought the Bible stories and characters to life again. As in the naive mythology of Christian children such figures as the guardian angel, the Virgin Mary, or even Father Christmas really and truly exist, so for little Marc only a flimsy screen divided his real world from the figures of the Bible: any night the prophet Elijah might have come down in his fiery chariot and landed in the backyard - only it was best not to watch him. This childlike naivete - that is, the ability to see through reality to the legendary background ..beyond it - is something Chagall has treasured all his life. There is nothing, it seems to him, to stop those heroes, holy men, and prophets from turning up in real life in a variety of disguises; all one has to do is recognize them, as Abraham did the angels.

In addition, another and much further-reaching idea, of ancient Jewish origin, lives in his heart. This is the idea contained in a wonderful Hasidic parable which tells that, when the flow of God's love poured forth into the basin of the earth, it shattered into the myriad fragments of individual things, in each of which still lives a spark of the divine love. Thus even the most ordinary and commonplace thing preserves a mythical aura, which, if one is a painter, asks to be expressed in the process of transforming visible things by means of the "chemistry" of painting. How much more, then, will not this mythical presence pervade animate life?

Out of such a variety of associations grew the pictures of the Biblical Message which were painted in Vence. They do not adhere very closely to the biblical text and often play quite freely with the biblical figures. The most astonishing example of this is offered by the picture here, King David. The figure of David was a perfect subject for Chagall's roving fantasy. Not only was he a brilliant hero, killer of lions, and conqueror of Goliath, but also a great lover who, in his love for Bathsheba - who bore him the king of all kings, Solomon - did not stop short of crime. He was also a great singer and dancer, who eased the heartache of King Saul with his music, sang the poignant lamentation for his friend Jonathan slain by the Philistines, and entered Jerusalem singing and dancing before the Ark of the Covenant.

This King David now appears like a sleepwalking giant, advancing in rhythmic dance steps and playing the harp - a mythical figure in an extraordinary setting in which dream and reality intermingle. Below, in the violet twilight before a side scene of Vence, advances a jubilant, gesticulating procession of godly Jews. To the right, however, floats a bridal pair such as had appeared in Chagallian imagery since 1947 as an emblem of yearning love - strangely elongated in a Mannerist fashion reminiscent of El Greco; also the coloring and buildup recall El Greco or Tintoretto. In the background, before a coulisse of Vitebsk outlined against a stormy sky lit by a golden moon, advances a bridal procession under a red canopy. The two festive processions - one celebrating divine love, the other nuptial love, in which, according to ancient Jewish teaching, the love of God is present - meet in a unity of space and time possible only in the artificial dimension of painting. It seems perfectly natural for such unusual scenes to call forth King David, that he may lead the procession before the Ark of the Covenant, singing and dancing as in days of old.