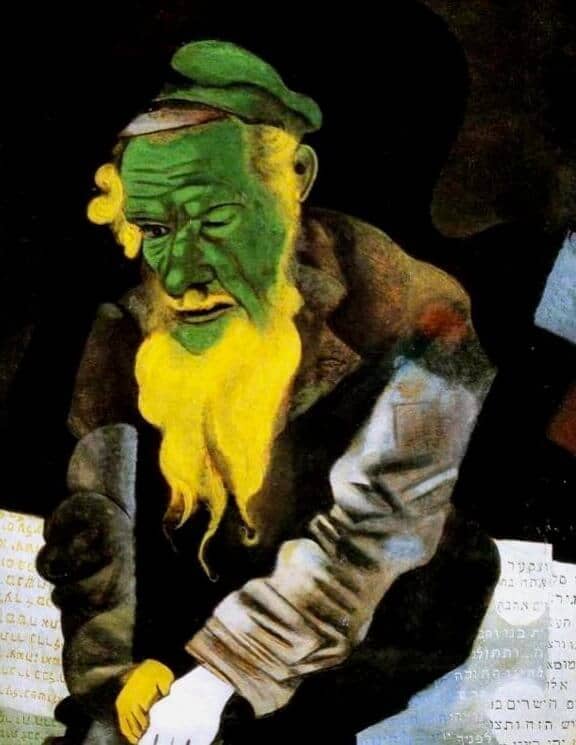

Jew in Green, 1914 by Marc Chagall

In 1914 Chagall was back in his Vitebsk. "Vitebsk is a place apart; a town unlike any other, an unhappy town, a boring town," he writes in his autobiography, where there were "humpbacked and leanbodied citizens, green Jews, the aunts During the latter years in Paris, his fantasy had been constantly occupied with the typical figures of suburban Vitebsk, and now he was confronting them in the flesh. In an impetuous urge to work he tried to lay hold of this real world. He portrayed everybody and everything: mother, father, himself, his sisters, uncles, aunts, all who were patient enough or who couldn't get away, the kitchen, the bakery, the living room, and people at their familiar household tasks. Together with his old friend and teacher, the painter Pen, he went out and sketched from life all the scenes in and around the town. He was preoccupied with creating the "documentary," as he liked to call it, and he lapped up this reality until he was full to the brim.

Strange guests - old beggars, peddlers with a sack over the shoulder, Jewish itinerant preachers - crossed the threshold of his father's devout and hospitable home. One day along came the "green Jew." He was the "preacher from Slousk," not a rabbi but one of those wandering Jews filled with holy inspiration, proclaiming the word of God, their lives full of extraordinary poetic radiance. There he sat, quiet and lost to the world, in front of the samovar in the living room. "I had the impression," Chagall recalls, "that the old man was green; perhaps a shadow from my heart fell upon him." So this is how he has painted him - as a meek old man slumped resignedly in his chair, with his green, inspired face illuminated by the gold of his beard. He seems to sit on a stone wall, as if it were a bench, on which are carved the holy texts in Hebrew script, the basis of his existence. Against the dark background plane, upon which the shape of the old man casts a wavering shadow, the green-golden face shines out like the countenance of the prophet Jeremiah, but the shabby Russian visored cap shows he belongs to the present age. The old man's jacket, colorless with age, also keeps him within the confines of reality. But look at the hands, one golden and one white, emerging from the crumpled sleeves! As they rest upon the man's knees, touching each other, the golden hand makes a connection with the face, sunk in meditation, while the other one, marble white, with its scanning forefinger seems to interpret and repeat the words of the chiseled script. By the unrealistic coloring alone, this pair of hands evokes the aura of deep meditation and the interpretation of the holy word which fills the whole being of the devout Jew. Despite all descriptive realism, these remarkable symbolic details are intended to make reality transparent.