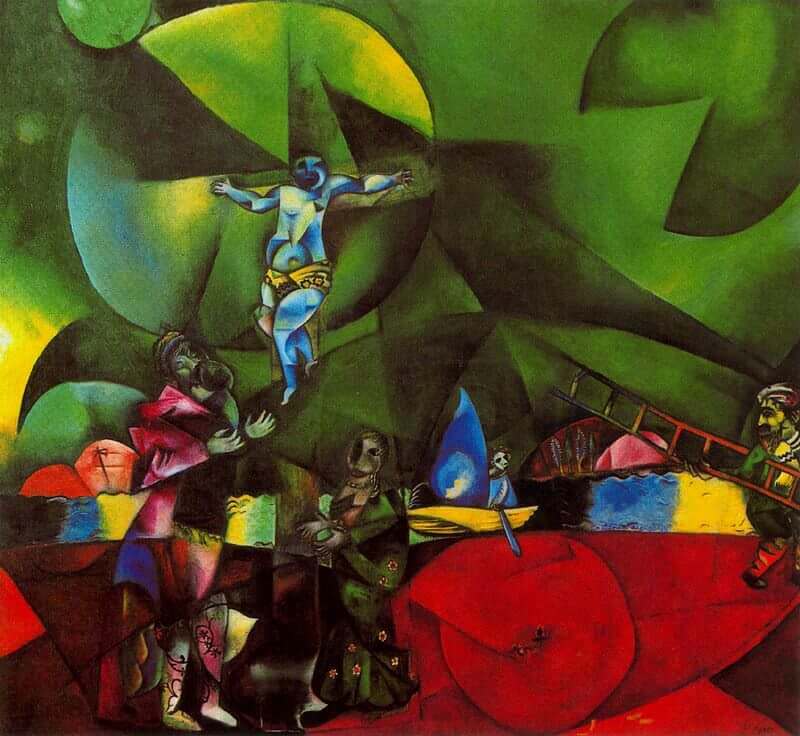

Golgotha, 1912 - by Marc Chagall

Having explored the construction of the picture, the painter could feel free to develop the colored crystal of the surface in as rich and meaningful a way as possible. The translucent color and the hierarchic structure of the forms may have stirred up in him, during this work, memories of rural glass paintings and of the solemn Russian Byzantine icons which, as a young painter, he had seen and admired in St. Petersburg collections, although in those days without effect on his personal style. Now, however, his own painting had come to a stage where he could really absorb the message of the icons.

At this time a crucifixion scene came to hand from among his early drawings, in which he had taken up this age-old motif of the icons and elaborated upon it a little. He used this scene as the basis for Golgotha, keeping a similar figurative inventory and arrangement. For poetic enhancement and the transformation of the worldly scenery into a further dimension, he relied entirely on his newly discovered rhythms of form and color.

That Chagall chose to paint a crucifixion as his first great religious composition need not surprise us. He had always held the figure of Christ in great veneration, regarding Him as the perfect man, who out of love took upon Himself the most absurd and at the same time the most wondrous act - His own death - for the world's salvation. As such He reappears time and again throughout Chagall's work, particularly during the bitterest times of persecution of the Jews, when He was the representative figure of the exemplary capacity for suffering by the believer, who despite the deepest sorrow does not despair of the love of God.

There is no need to overemphasize the religious background. There was a need to express something visionary; the discovery of the drawing supplied the theme, and then Chagall left himself open to the wonderful suggestions which came in the course of painting. In a conversation with Franz Meyer, Chagall recalled a situation during the creation of the picture: "Strictly speaking, there was only a blue child in the air. The Cross was of less interest to me." What did interest him was the vision. That the appearing vision is of the greatest importance is shown by the central figure itself, which is not intended as the crucified at all, but as one resurrected into childhood, and at the same time as a messenger of salvation, descending from above.