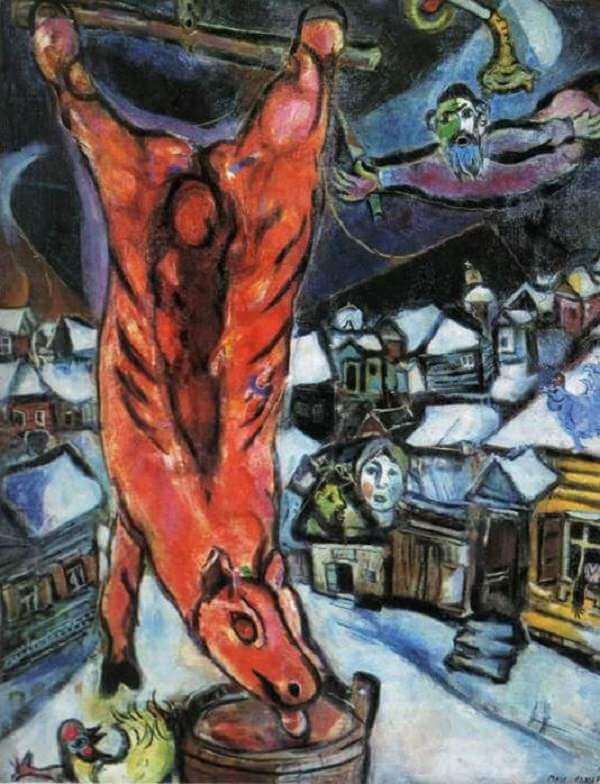

Flayed Ox, 1943 - by Marc Chagall

The same monumental and allegorical power that we observed in The Falling Angel is displayed in Flayed Ox, which was painted at roughly the same time. This painting too goes back to an earlier motif, which Chagall had begun to work on in 1929, in remembrance of Rembrandt and also most probably of Soutine, who was his studio neighbor in La Ruche during the first Parisian years. But whereas in the first painting of 1929 the animal's body was arranged beside a bouquet of flowers and in front of a bright, wide landscape - in an impasto style with attention to color values, so that the painterly and still-life elements were predominant - in Flayed Ox it is once again the metaphoric quality and the color which elicit from the stark motif a parable of fate. Since the days of his childhood, when, during drives with his uncle Neuch the cattle dealer or in his grandfather's slaughterhouse, he had seen animals killed in the Jewish fashion, the slaughter of the animal had held an uncanny fascination for him, like the ritual of a sacrifice which had a deeply hidden meaning and for which a means of expression would eventually have to be found. His first studio in La Ruche was close to the slaughterhouses of Paris, and he recalls, "Dawn is breaking. Somewhere not far away they start cutting the throats of the cattle, cows bellow, and I paint them."

The hidden meaning which he wanted to paint now emerges as a picture and as a parable of the times. The gigantic, crucified body of the animal hangs before a nocturnal scene. In the skinned, raw flesh is still the agony of wanting to live, shown by the greedy lapping of its own blood. At the left a terrified cock rushes away. The drama takes place in front of a Russian village on a clear, bright, winter's night; against the background of huts piled up like boxes in the cold light of the snow, the lonely flayed colossus appears, like a sacramental offering, as a bloody banner and apotropaic vision of terror which contrasts to the peace of the place. The head of a peasant woman gazes compassionately at it across the roof of a house. The limp wing of an exhausted clock dangles out of a front window, as if time were ready to die. The sky is dark and hard like hammered metal. The surface is solid as a wall, as in The Falling Angel, and in the compact layers of its structure has lost all illusionist character. At the top right occurs a most unrealistic event which shifts the entire ensemble of figures and things, seemingly halfway realistic, to a visionary realm. Into the picture flies a bearded Jew, with outstretched arms, as a messenger of terror. As his bloody knife indicates, he is the slaughterer who has performed the sacrificial ritual. But he is also the terrified prophet who proclaims the terrible truth that only in the bloody sacrifice of the innocent does man come to recognize reconciliation and peace. Above him the burning candle, the Chagallian emblem for peace, warmth, and domestic tranquillity, threatens to go out. Now we can see more clearly that the picture is concerned with a new metaphoric interpretation of the crucifixion theme. The image of the crucified creature becomes a representative, universal sign for the message of the crucified Christ, detached from the narrower religious associations. During the war years, from 1940 on, Chagall painted many pictures with scenes of devastation - villages on fire, people fleeing - some of which depicted the crucified amidst human misery. None of these, however, has the rapt solemnity and timeless symbolism which we find here. The whole agony of the times has been gathered into one intense, definitive, and portentous metaphoric picture.