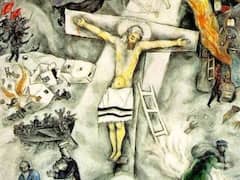

Easter, 1968 - by Marc Chagall

Religion is never out of Chagall's mind. He carries his faith around with him wherever he goes, just as the wandering Jew - that recurrent figure of his personal mythology - carries his sack. The biblical message and the festive

circle of the Jewish year inexorably demanded of him that he should constantly bear witness; this theme runs throughout his art.

In Easter of 1968, painted in the studio at Saint-Paul, the theme appears in the highly dramatic coloring with which the painter was wholly occupied at this period. Here again black and white set the basic tone, which is

heightened to a visionary light by the mysteriously shining red plane. Like a window, it opens on a blood-red star, with a cold complementary green enhancing its fiery glow still further.

Whenever the Jewish religious festivals occupied Chagall's imagination, the memory of his homeland seemed to return of its own accord, so closely were the expectations of his childhood governed by the Jewish festive rites. So

here too we find the Russian village, the suburb of Vitebsk. There are the wooden houses, huddled together, a little lamp glowing faintly in one of their windows; a woman steps outside the door, a winged creature peeps over the

rooftop, a solitary couple wanders up the village street in the dusk. An enormous white moon pours its cold light like snowffakes over the houses. To the left, four old Jews keep the feast of the Passover, huddled in their prayer

shawls beneath this icy light. They sit in the open field, above which a stormy sky drives the thin crescent moon. How exposed and threatened is their existence and their festive ritual in this coldness! But once again an angel

rises up and with its wings covers the menace of the blood-red star. Peering out of the dark lattice, its yellow color transfiguring the ghostly light and also affecting the angel, an animal's head observes the phenomenon in the

heavenly zone with astonishment.

There is a great deal of menace in this picture, much compassion for suffering, and only a little consolation. The drama of threatened human existence, saved only by its faith, is completely bared. It is heightened to a universal

allegory by the constructive power of color, and it may well be that the glowing colors of Chagall's sacred windows - the effect of the black strips of lead against the translucent stained glass - put Chagall on this road to

dramatic color effects in painting.